Note: This is part of These Girls On Film’s coverage of TIFF Bell Lightbox’s On the Road: The Films of Wim Wenders

Wings of Desire will be playing at TIFF Bell Lightbox on March 5th

Wings of Desire

I say it often and I say it loudly, it is a horrible despair we feel when we realize that we can not possibly watch all the films we want to in one lifetime (it’s the same with books). It becomes ever more palpable when you see a film that is reflected in so many others. The chance that you’re missing a nuance or that there is so much more beyond a scene, in the history of its making, or in the story of the evolving filmmaker, that it tugs at the heartstrings: we don’t have a limitless amount of time here, nor enough eyeballs.

This is going to be all fragmented, much in the same way as I’ve seen Wim Wenders’ films for the past two weeks. I say fragmented because this is my first time exposed to more than one of his films (Paris, Texas was the only film I’d seen before of his – and is still one of my top favourite films), even though many have often mentioned or assumed I have seen all of his work already. Wenders has indirectly influenced film thoughts through other works and for that it is with a great surprise pleasure that I find myself wanting to write about these two films. But I want to write about them in the way that I saw them which is why I’ve written this up as thoughts that came into my mind while going over my notes.

I’ll be talking about Paris, Texas and Wings Of Desire exclusively, but we’ll see where this goes.

I bounce off of these two articles by Roger Ebert, somewhere in there, so include in the links in case I’ve spun off an idea or mis-sourced it.

- http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-paris-texas-1984

- http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-wings-of-desire-1988

**************************

2nd Chorus Mexico City Blues by Jack Kerouac

Man is not worried in the middle

Man in the Middle

Is not Worried

He knows his Karma

Is not buried

But his Karma,

Unknown to him,

May end —

Which is Nirvana

Wild Men

Who Kill

Have Karmas

Of ill

Good Men

Who Love

Have Karmas

Love Song by Rainer Maria Rilke

How can I keep my soul in me, so that

it doesn’t touch your soul? How can I raise

it high enough, past you, to other things?

I would like to shelter it, among remote

lost objects, in some dark and silent place

that doesn’t resonate when your depths resound.

Yet everything that touches us, me and you,

takes us together like a violin’s bow,

which draws *one* voice out of two separate strings.

Upon what instrument are we two spanned?

And what musician holds us in his hand?

Oh sweetest song.

******

Wenders’ Paris, Texas (aka PT for this essay) starts with the dissonant slide guitar twang of Ry Cooder‘s soundtrack. The viewer is unsure of the mood of the tune and the title block comes up stark red amongst a black background. The first thoughts are of blood and panic. Then the familiar country-tinged strum of a guitar releases the tension. The journey of the viewer begins with stunning panning shots swooping sideways, the vantage point of a hawk. The hawk scans for prey and lands, eyeing our protagonist Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), disoriented and walking determinedly in the desert.

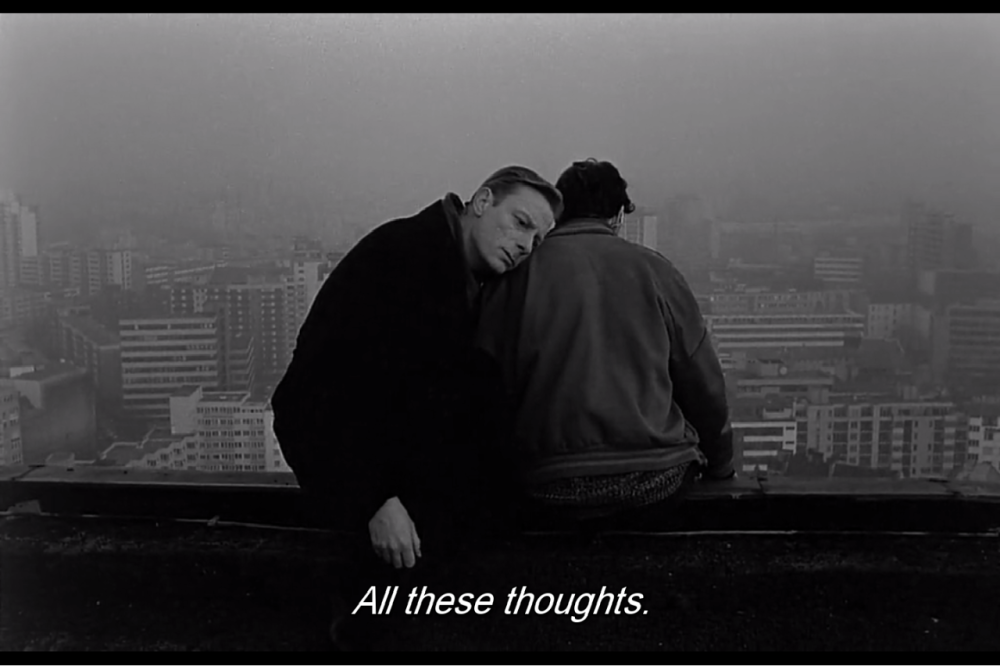

Wings of Desire (aka WofD for this essay) opens to the voice of Damiel (Bruno Ganz) softly singing a lighthearted tune as he writes “when the child was a child,” and fades into the tense sounds of a deep cello and the staccato of a violin. It is soothing and playful at first, only to become sad with the start of the soundtrack. It feels like the beginning of an old 1920s tragedy. While PT begins with a low tracking shot from the side, WofD opens with a high tracking shot from high above the sky overlooking buildings in Berlin. It is the vantage point of high flying birds, or as in this case, angels who watch, record, and comfort, but are unseen.

What caught me the most about PT is the rhythm with which it flows. Writer Sam Shepard infuses the script with a Jack Kerouac beat poet droll; steady in its progression, like the unknown confidence of Travis’s steps. It is only water and the need to continue that stops him, inadvertently making it possible for his brother Walt to find him. For the first little while the screen is filled with ideas of Travis having amnesia and being mute, thus we are only offered visuals and clues. We know Travis can talk, but for some reason, he chooses not to.

Meanwhile, WofD is a poetic narrative mixed with visual essay of Berliners thinking through their day. Damiel stands atop a triumphant statue and his angelic wings fade, an affect that evokes Maria’s transformation scene in German director Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

We hear the soft harp from the Jürgen Knieper soundtrack and Damiel surveys Berlin below where only children can see him, and they do in awe. The whispers of thoughts of the people and there is a flood of information, but between the many angels that inhabit the city, all is collected calmly, like priests listening to confessions. The words in the thoughts are from a written and oral language shared amongst all of the city’s citizens. Their words communicate their inner spirits just like the spoken and unspoken cues by the angels. Wenders was partially inspired by the Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry saying:

Wings of Desire

The script reads like poetry, fragmented and open to interpretation for the listener. The pace of the film is slow, but doled out like the city stretching out its wings in the metaphors extolled in the whispers of its people.

But unlike PT that starts off with giant colourful visuals, WofD is replete with infinite personal narratives that colour the black and white screen.

Paris, Texas

Wings Of Desire

The angels’ see the world as black, white, and grey, while the humans around them see the everything in bright colours, much like the palette in the scenery in PT.

Much can be said about the American road movie for PT with its giant expanses revealing a search for something in the horizon, much like the cowboys of the old west. However, Travis is undecided. He’s sure that he must travel somewhere and make amends for his past to find direction in his future. At first, his destination is to Paris, Texas where his father says he met his mother, as part of a long told story that once started off as a joke in its romanticism. Then he veers off his journey to find his son, Hunter (Hunter Carson), so he could try to be a father to him. After a bit, he realizes that he would like to find Jane (Nastassja Kinski), Hunter’s mother, to reunite them. In that search, Travis becomes closer to his son and they exchange stories: Travis about his father and Hunter about science and space travel. The idea of space travel is quite poignant in the entirety of the narrative in PT because while the young boy looks towards the sky in wonder, old Travis doesn’t see any reason to get off the ground. The space he wants to explore is within himself.

Paris, Texas

Travis seeks to strip himself of a world with language and people. He belongs somewhere and also not anywhere.

In WofD, angel Damiel has witnessed the world through many stages along with his fellow angel Cassiel (Otto Sander). They join a congregation of other angels listening in to the thoughts of people in the Berlin State Library. What I find interesting in the contrasts between PT and WofD, is that PT concentrates on the forgotten and remembered histories of the characters in the giant expanse of the desert, a place where history places itself in the spirits of the people that inhabit it.

WofD‘s scenes are of a city built among the ashes of a city before it, and scenes within the state library which also has been survived been rebuilt, are a compilation of a story of a city undergoing a continual search for identity, especially within its own population. The scenes with an elderly Holocaust survivor, Homer the aged poet (Curt Bois) looking through old texts are some of the most meditative and poetic monologue in the film. It’s one of the many indoor scenes that are striking amongst Brutalist architecture.

HOMER THE AGED POET: “Must I give up now? If I do give up, then mankind will lose its storyteller. And if mankind once loses its storyteller, then it will lose its childhood.”

In contrast, PT‘s script is sparse, but has the subversive undercurrent of philosophy. Hunter says to Anne (his uncles’ wife who has raised him):

“Do you think he still loves her?”

ANNE: “How would I know that, Hunter?”

HUNTER:”I think he does.”

ANNE: “How can you tell?”

HUNTER: “Well, the way he looked at her.”

ANNE: “You mean when he saw her in the movie?”

HUNTER: “Yeah. But that’s not her.”

ANNE: “What do you mean?”

HUNTER: “That’s only her in a movie…a long time ago…in a galaxy far, far away.”

Later on, a simple walk turns into the most touching portrait of fatherly love.

The everyday philosophical epiphanies of a child become the thread that ties the poetic visuals and silent narratives in PT.

Paris, Texas

It is in WofD where thoughts of existence are obscured by the need to discover living life especially for Damiel who is eager to feel things as he’s observed them without comment for all of eternity. He seeks limits and grounding and never questions why (much like Travis doesn’t want to explore outside. He’d rather explore inside himself).

Cassiel witnesses a suicide and it affects him deeply. He spends the rest of the film mostly silent on contemplation of Damiel’s want for mortality. In turn, Damiel falls in love with a trapeze artist Marion (Solveig Dommartin). She becomes a calling to him, or rather an anchor to hold him in time out of the despair of forever.

Wings of Desire

Meanwhile, in PT, Jane is not a source of grounding, but rather a springboard for Travis to find himself. By returning Hunter to his mother, Travis isn’t making amends, rather he’s stringing up all the threads so he can go on in search of himself with no loose ends. Although the famous and most tragic scene in the film is of Travis telling Jane a story behind a peep show one way mirror, the most telling are two scenes.

Travis walking along a bridge:

A crazy (or sane!) man warns out loud to passing traffic about impending doom. The shot is brilliant because it encompasses the unheard screams of those in solitude in the valleys of Los Angeles. Cars everywhere and people hardly walk (as Hunter says earlier in the film). The desolation among the giant expanses provoke the soul searchers and among them those that can search (Travis) and those that are too overwhelmed by its revelations (crazy man).

Then there is the final shot in PT (I’ve started it at the part I’m talking about).

Travis looks on at the reunion between son and wife. This is all without him knowing if that reunion will work or not or if Jane can handle motherhood at the moment. He just needed to make this happen so he could move on.

It’s this interesting contrasting views of free will that made me love watching these two films together. While PT has a man with an unspoken or unremembered mission, WofD has an angel taking life by the horns. Damiel bursts out of the periphery of Berlin to continue along with its story whether it be infinite or finite, he has become a part of it with Marion. Their love and partnership is the story among other universal stories in Berlin’s past, present, and future. This is why scenes of ruin, war, renewal, and reconstruction are big part of the scenery of WofD.

I must stop here, since there is much more I’d like to explore in WofD including Peter Falk’s character and that of the architecture so beautifully rendered on the screen. More of that will be explored over at Next Projection next week in my full analysis of Wings of Desire.

This is what I love about film. You can find new things in the old and find the old threaded in the new so well. With Wenders I’ve found a great deal of dactylic language in its visuals and scripts. His films can be long, but they are journeys of personal, universal, and spiritual ideas that require poetic cinematographers (Robby Müller and Henri Alekan) and working philosophers (Sam Shepard – adptn: L.M. Kit Carson and Peter Handke and Richard Reitinger). So far, Wenders films haunt the mind after the watch and the re-watch provokes endless thought, much like the work of an involved novel. It might not exhaust the body, but exorcises the soul to seek for something more than what’s presented to the viewer’s eyes. There’s world out there beyond the viewer’s eyes and it may lead to the forever in the present.

NICK CAVE: From her to eternity. – WofD

************

- GEOGRAPHY AND TIME: THE SEARCH FOR PLACE IN ‘PARIS, TEXAS’ AND ‘WINGS OF DESIRE’

- Wim Wenders On Claire Denis

- German film director Wim Wenders takes the road less traveled away from blockbuster thrillers toward poetic and philosophical destinations